Words [ Sue Kendall ]

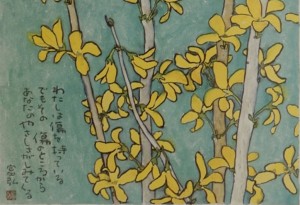

Like beautifully colored gems extracted from a dark cave, original illustrations created for the Clinical Center’s popular Medicine for the Public (MFP) lecture series have been pulled from storage, framed, and put on display in Gallery I.

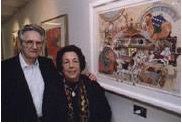

The Medicine for the Public lecture series was created by the CC in 1977, and has been presented every fall since. Lectures on disease topics are presented by NIH scientists and are illustrated by original art that helps translate medical terminology into understandable concepts.”I was astonished at this wonderful collection of art that has been here all this time,” said Lillian Fitzgerald, of Fitzgerald Fine Arts, curator for the CC’s art galleries.

“Anatomy of Memory” lecture,1989

In the spirit of the new millennium, Fitzgerald wanted to pull together a collection of art that reflected NIH’s history. During discussions with Colleen Henrichsen, chief of CC Communications, which runs the lecture series, and Linda Brown, of the Medical Arts and Photography Branch (MAPB), Fitzgerald said the idea of displaying the MFP art quickly took shape because the pieces fulfilled several goals at once.

“The illustrations are appealing from an artistic perspective, and they reflect artistic styles over the past 20 years, but they also depict a history of NIH’s work,” she said. Lecture topics are selected each year on the basis of current research, new findings, and public interest.

With over 180 lectures in 23 years, there are an estimated 9000 visuals in storage. “We couldn’t sort through all of them, so I selected some that particularly appealed to me,” said Fitzgerald. Brown pointed out that “we could change the exhibit every month for 10 years and not run out of illustrations.”

Originally titled “Medicine for the Layman,” the series was developed as a means of reaching out to the general public with information on clinical research, and to make people aware of what NIH does and how it contributes to the public health of the nation.

“The challenge was to create a means of conveying complex medical and scientific information to nonscientists. This was achieved by creating understandable, recognizable, and sometimes humorous visual images to accompany the lecture,” said Henrichsen. As with any work of art, sometimes the images connected with the viewer, and sometimes not. But always the artistic quality remained high.

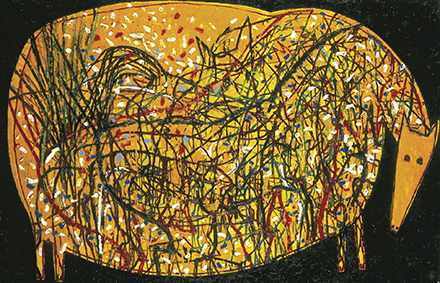

“Genetics of Cancer” lecture, 1988

“When we selected artists for Medicine for the Public, we always looked at the quality of the art first,” said Ron Winterrowd, retired chief of MAPB. “Then we looked at which artists had the ability to work effectively with the doctors. And then, of course, they had to be able to meet the due date.”

After the lectures were over, many of the illustrations reappeared in a series of booklets developed from the talks. Although budget constraints have stopped development of illustrations for current MFP lectures, a new use for the art from past lectures is on the horizon.

“Lillian presented the idea of decorating selected areas of the new hospital with some of these illustrations,” said CC Director Dr. John Gallin. “We thought it would be an excellent new use for these interesting and beautiful images. Also, since the art is already owned by the Clinical Center, there’s a cost savings from not having to purchase new pieces.”

The MFP art will be on display through March 1 in Gallery I, which is along the diagonal hallway that leads from the North Lobby to the Center Lobby elevators.

The Clinical Center maintains three other galleries and three sculpture cases. Shows are changed six times a year.

“Obesity” lecture, 1977

“There is often an NIH or CC connection in the shows,” Fitzgerald said. “In addition to the MFP art, the current show has works by the wife of an NIH doctor and a CC nurse who was so inspired by the galleries that she returned to school to study art.” An exhibit last year showcased art by the mother of an NICHD doctor.

In addition to providing inspiration and enjoyment, the galleries benefit CC patients and their families. According to Crystal Parmele, art director for the CC galleries, “We ask that the artists make their works available for sale, with 20 percent of the price donated to the Patient Emergency Fund. Only in special instances are pieces not for sale.”

The MFP illustrations, however, represent one of those special instances. They will remain in the CC’s permanent collection.

“Carousels of Sunshine,” a motorized, lighted, musical work of art, was donated to the Clinical Center by artist Arthur A. Plant and his wife Theresa, of Columbia, Md. The carousel hangs in the phlebotomy waiting area, near the Admissions Desk, where it delights children and adults alike as they wait for their blood draws. This is the 12th carousel Plant has created and donated to hospitals over the past 7 years “because of my belief in the healing powers of music, art, and beauty,” he said. Over 50 people attended a reception last month in the Medical Board Room, where Plant received a certificate of appreciation for his donation.

“Carousels of Sunshine,” a motorized, lighted, musical work of art, was donated to the Clinical Center by artist Arthur A. Plant and his wife Theresa, of Columbia, Md. The carousel hangs in the phlebotomy waiting area, near the Admissions Desk, where it delights children and adults alike as they wait for their blood draws. This is the 12th carousel Plant has created and donated to hospitals over the past 7 years “because of my belief in the healing powers of music, art, and beauty,” he said. Over 50 people attended a reception last month in the Medical Board Room, where Plant received a certificate of appreciation for his donation.

Jun

11